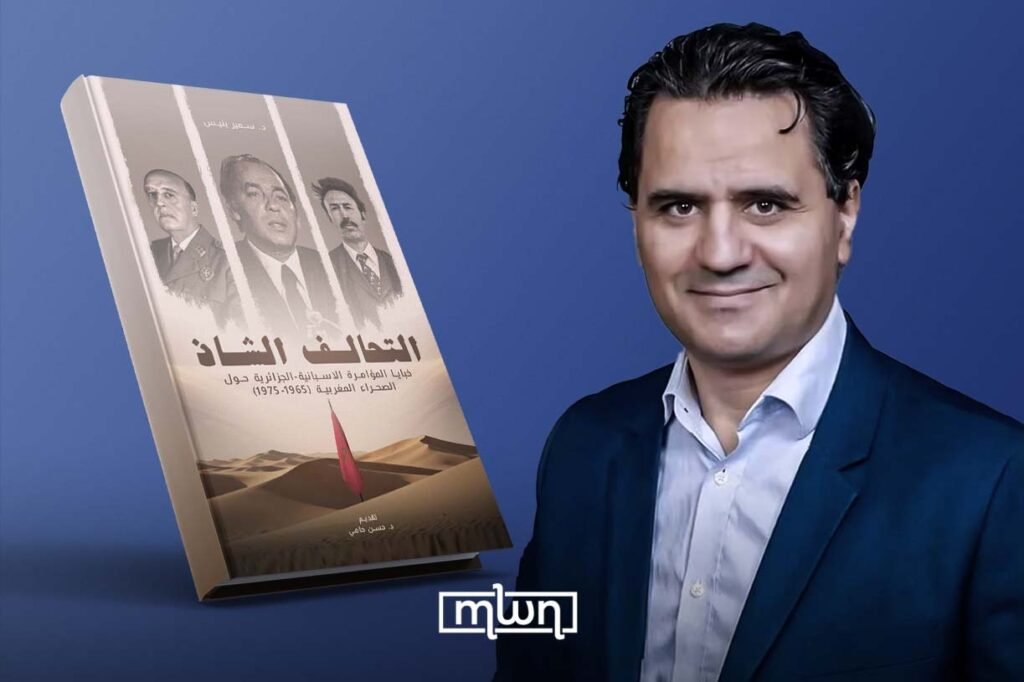

Rabat – Moroccan scholar Samir Bennis has released a new book on the Sahara dispute, dissecting yet another little-known historical dimension of what he cogently presents as a long and winding tale of foreign maneuvers to prevent Morocco from recovering its lost southern provinces.

The book was released on Thursday this week, under the self-explanatory title of “The Unholy Alliance: Inside the Spanish-Algerian Conspiracy Over the Moroccan Sahara (1965-1979).”

Bennis dedicated the book as a commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the Green March.

The book comprises fifteen chapters across 512 pages, in which the author mobilized primary documents that had been overlooked not only in Moroccan academia and media circles but also in the West.

He examines Spain’s decades-long attempt to impose a new political reality that would allow it to maintain its colonial grip on Morocco’s southern provinces. To that end, the book also explores the emotional and psychological dimensions that have shaped ties between Rabat and Madrid.

For Bennis, this development is essential to understanding the chronic tensions that have overshadowed ties between the two countries since Morocco’s independence.

Indeed, this book effectively documents how psychological factors were among the main motives behind Francisco Franco’s obstinacy and his refusal to reach a mutually acceptable solution on the Sahara.

The book also navigates the strategy adopted by King Hassan II starting in late September 1975 to regain the political initiative he had lost in 1966. Faced with the Spanish-Alegarian collusion to undermine Morocco’s struggle to retrieve its Sahara, the King’s new strategy eventually succeeded in compelling the Spanish government to come to the negotiating table to reach a solution that would ensure Morocco’s recovery of its sovereignty over the Sahara.

With extensive research and academic expertise, Bennis painstakingly explores here the roots, evolutions, and geopolitical implications of the Sahara dispute. He thus offers academics, political elites, and diplomats a comprehensive understanding of the milestones that have shaped this regional conflict, starting with how King Hassan II pulled off the organization of the Green March, the strategic masterstroke that saw him crush the unholy alliance between Algiers and Madrid.

Glimpse into the chapters

The opening chapter paves the way for readers to explore the Sahara question and how it emerged in the aftermath of Morocco’s independence.

It also showcases how Spain’s lingering colonial presence was motivated by strategic considerations, including securing the Canary Islands and exploiting maritime resources.

A fine connoisseur of Spain’s history and political culture, Bennis demonstrates how Spain’s continued colonial presence in the Sahara was dictated by a deeper psychological refusal to accept the end of its power in Morocco.

Meanwhile, chapter II sheds light on Morocco’s consistent demonstration of good faith in its efforts to rebuild trust with its neighbors, particularly Algeria and Mauritania, in the late 1960s and 1970s.

While several initiatives sought to diplomatically isolate Spain, the chapter shows how, under Houari Boumediene, Algiers had already adopted a strategy that set the stage for deeper geopolitical rivalry.

Chapter III, for its part, dives into Madrid’s simultaneous efforts to consolidate its presence in the Sahara, detailing how Spain created the Saharan local assembly and worked to construct a separate “Sahrawi identity” aligned with its long-term plans.

The book’s third chapter also shows how Spain exploited tensions between North African countries like Algeria and Mauritania, as part of an imperialist scheme to keep the territory under its control.

Having set the stage in these earlier chapters, Bennis takes his readers to the heart of the shifting sands of alliances, counter-alliances, historico-emotional grievances, secret dealings, and last-minute betrayals that have conspired to prolong Morocco’s march to reunite with its southern provinces.

Do not miss the opportunity to secure a copy and gain deeper insight into a long-standing dispute that has reached a decisive turning point in recent months, as more than 120 countries now recognize Morocco’s Autonomy Plan as the most or only credible route to a lasting political resolution of the Sahara dispute.

In fact, the book arrives just months after the UN Security Council consecrated Morocco’s autonomy proposal as the best path to a realistic and sustainable political solution. With its Resolution 2797, which it adopted last October, the UN’s most consequential body embraced the Moroccan initiative as the most genuine political framework for negotiations to end the Sahara saga.

Adding to this momentum is the recent round of US-facilitated talks in Madrid, which brought together all concerned parties in the Sahara dossier, including Algeria.

Quite impressively, Bennis’s encyclopedic exploration of a critical historical dimension of the Sahara question comes a little over a year after the publication of his book on what he called “the self-determination delusion.”

Equally profound and holistic in its examination of schemes and maneuvers that have defined the legal, political, and diplomatic struggles over the meaning and components of self-determination, the book offers a searing and diligently researched critique of the misleading narrative in media, political, and intellectual circles over the history of the Sahara.

As such, one could read the two books, while separate, as integral and perhaps inextricably linked parts in Samir Bennis’s lifelong quest – or mission – to give Morocco, especially Moroccan diplomats, scholars, journalists, and students – the intellectual tools it needs to cogently dispel the prevailing misleading narrative over the history, present, and future of the Sahara.

Bennis has long said, both in his regular articles for Morocco World News (of which he’s the co-founder) and interviews with the Moroccan and international press, that his goal is to get the historical record straight on the fact that the Sahara is fundamentally a Moroccan province.

Reading this book and the volume that preceded it, it is clear that Bennis has largely achieved that goal. Now, though, it remains to be seen whether the makers of Moroccan diplomacy will heed his urgent call on Morocco to start investing in the narrative front, which is the only venue left to Algeria’s strategists and Spain’s Morocco-bashing politicians and intellectuals after their separatist cause has lost the historical and diplomatic battles over the Sahara.