Marrakech – After the caftan, after zellij, after couscous, after the Atlas Lion, and after the online endless tug-of-war over symbols and digital archaeology of “who owns what,” apparently, it was only a matter of time before the turn came for argan too.

Not through scholarly discourse or cultural exchange – but through the most insidious of modern battlegrounds: a viral livestream, a street vendor’s calculated pitch, and a phrase engineered for algorithmic amplification.

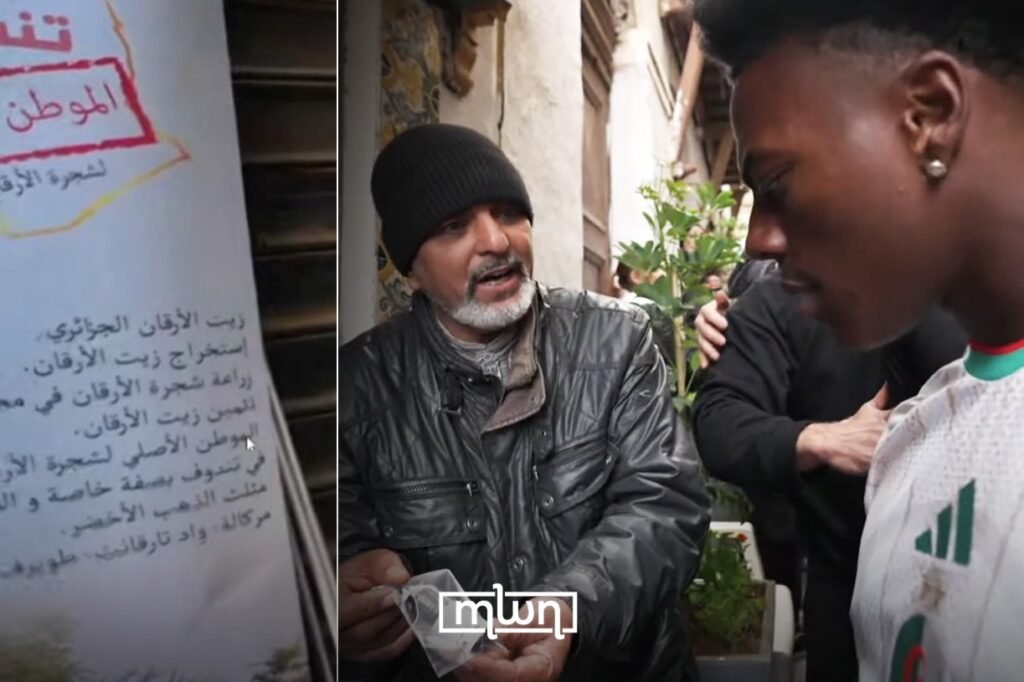

During one of his Algeria series of streams, IShowSpeed met a seller who boldly proclaimed “natural Algerian argan” to millions of viewers, brandishing a sign that falsely stamped Tindouf as its origin. As has become customary for Algeria over the years, this was yet another blunt act of narrative forgery performed in plain sight.

In other words, this wasn’t merely commercial opportunism. It was cultural piracy in real-time: a branding hijack, a narrative theft, and the latest manifestation of a now-familiar pathology in North African identity politics.

View this post on Instagram

A theft broadcast globally

IShowSpeed’s Algerian adventure, part of his breathtakingly ambitious 20-country African tour compressed into just 28 days, was supposed to showcase the continent’s diversity to his 50 million followers.

The American YouTuber, born Darren Watkins Jr., has built his empire on spontaneous energy and unfiltered cultural immersion – exactly the kind of authentic content that transforms unknown destinations into global phenomena overnight.

His livestream from Djanet garnered over 3 million views in five hours – a marketing windfall that tourism boards worldwide would pay millions to achieve, especially for a country that attracted barely 3.5 million tourists in 2024. In his Algiers stream, the American YouTuber was greeted by swelling crowds with near-messianic fervor, as if a long-awaited savior had arrived.

The footage captured everything Algeria’s tourism ministry could have scripted: Speed donning traditional Tuareg attire, sharing meals with locals, dancing in the streets, and expressing genuine wonder at the Sahara’s vastness.

His infectious enthusiasm for Algeria’s Saharan landscapes and warm hospitality provided exactly the kind of soft-power projection that nations crave in an attention economy where viral moments translate directly into visitor arrivals.

The timing couldn’t have been more fortuitous. With reports suggesting Speed’s itinerary includes Morocco for tomorrow’s AFCON 2025 final between the Atlas Lions and Senegal – a match that could see Morocco’s golden generation claim a continental crown that has eluded the kingdom for half a century – Algeria had captured a coveted spotlight moment.

Speed’s journey from the Sahara’s ancient dunes to Rabat’s modern stadiums would have created a perfect North African narrative arc, showcasing regional diversity while respecting distinct national identities.

Until, apparently, someone decided that wasn’t enough. Why settle for showcasing authentic Algerian heritage – the stunning Tassili n’Ajjer landscapes, the rich Tuareg culture, the genuine warmth of Saharan communities – when you could simply claim someone else’s?

Botany leaves no room for spin

In that calculated moment when argan was rebranded as “naturally Algerian,” authentic cultural exchange was sacrificed for opportunistic appropriation. Speed’s goodwill tour became an unwitting platform for heritage theft, transforming what should have been a celebration of Algeria’s legitimate treasures into yet another episode of cultural piracy.

This moment crystallized something profoundly disturbing about Algeria’s approach to regional heritage. Here was argan – Morocco’s UNESCO-protected treasure, scientifically documented as Argania spinosa, endemic to southwestern Morocco for millennia – being casually rebranded as “Algerian” for global consumption.

The audacity wasn’t just commercial; it was existential. In that fleeting exchange, we witnessed the mechanics of cultural appropriation operating at internet speed: steal, rebrand, broadcast, repeat.

The incident exposes a deeper malaise. A simple Google search, a basic ChatGPT inquiry, even a cursory Wikipedia consultation confirms what the scientific community has established beyond dispute: argan is exclusively Moroccan.

The tree exists nowhere else on Earth naturally. Morocco’s southwest region – from Agadir to Essaouira to Taroudant – represents the entirety of argan’s natural habitat. This isn’t contested scholarship requiring archaeological evidence or linguistic analysis. It’s botanical fact, as verifiable as the location of the Amazon rainforest or the Sahara desert.

This brings us to argan’s indisputable Moroccan origins. The tree has been Morocco’s ecological and economic cornerstone for centuries. Over 2.5 million Moroccans depend directly on argan for their livelihoods, with approximately 50,000 women working in cooperatives that have grown from 111 entities in 2000 to over 4,500 by 2019.

Morocco’s legal framework protects argan through Geographic Protected Indication status since 2010. UNESCO recognized argan oil production practices as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2014. The May 10th International Day of the Argan Tree, established by the United Nations in 2021, celebrates Morocco’s stewardship of this unique ecosystem.

‘Existing’ heritage left to rot

The desperation sinks into pathological territory when one examines Algeria’s handling of its own so-called “legitimate” argan heritage in Tindouf. The region is historically a Moroccan territory, yet this alone is an uncomfortable reality so politically toxic that even Boualem Sansal, one of Algeria’s most prominent intellectuals, was imprisoned for a year simply for articulating it aloud.

Despite possessing actual argan groves – albeit severely degraded and marginalized – Algeria has systematically neglected this authentic patrimony while fantasizing about appropriating Morocco’s thriving industry.

The state-controlled TSA news agency’s January 2025 proclamations about “reviving Algerian argan” read like the fevered delusions of a cultural kleptomaniac. The kind that celebrates phantom plantations even as the real Tindouf arganeraie withers from decades of bureaucratic abandonment, overgrazing, and ecological vandalism.

This is the profound sickness of a nation that would rather steal another’s flourishing heritage than nurture its own struggling legacy. It speaks of a country so psychologically fractured that it prefers the narcotic high of appropriation to the arduous work of authentic cultivation.

Algeria might possess actual argan trees, yet chooses to peddle counterfeit claims on global livestreams rather than invest in its own botanical inheritance. This isn’t mere opportunism; it’s cultural necrophilia – the compulsive violation of living heritage to animate the corpse of one’s own neglected identity.

Appropriation masks an identity vacuum

But this argan appropriation reveals something more troubling than mere commercial opportunism. It reflects the deeper identity crisis that has plagued Algeria since independence – a crisis so profound that it compels the systematic appropriation of neighboring cultures to fill the void where authentic national identity should exist.

Unlike Morocco with its twelve centuries of dynastic continuity or Tunisia with its coherent Bourguibist project, Algeria emerged from 132 years of French settler colonialism with no institutional anchors, no unifying political mythology, and no consensus on what it means to be Algerian.

The result is what scholars describe as a permanent identity crisis. And this is manifested in linguistic schizophrenia, ethnic marginalization, civil war, and recurring popular uprisings that expose the hollowness of official nationalism.

The Regency of Algiers (1516-1830) functioned as a semi-autonomous Ottoman vassal state governed by elected deys – a “military republic” without hereditary succession. While some historians like Mahfoud Kaddache consider the Ottoman period “catalytic to modern Algerian development,” others, including John Ruedy, argue the ruling minority remained a “foreign military clique” that never indigenized.

French colonization of Algeria (1830-1962) was qualitatively different from the protectorates imposed on Morocco and Tunisia. While France preserved the Moroccan Sultan and Tunisian Bey as nominal rulers – maintaining traditional institutions – Algeria was declared an integral part of metropolitan France.

Algeria was annexed and subjected to assimilationist erasure that dismantled Ottoman structures, confiscated land, and produced what scholars describe as “cultural genocide.”

The territory’s borders, the very name “Algeria/Algérie,” were formalized by French conquest – General Schneider’s October 1839 letter replaced “French Possessions in North Africa” with the modern designation.

As historian Sylvie Thénault documented, the French refused even to say “Algerians,” instead using “indigènes” or “musulmans,” because acknowledging “any collective identity capable of constituting a nation was denied.”

Frantz Fanon, working at Blida-Joinville psychiatric hospital, concluded that many psychiatric disorders among Algerians were “due to the unequal colonial relationship that permeated every aspect of Algerian society.”

In The Wretched of the Earth, he described colonial Algeria as “a world cut in two,” where Algerians existed in a “zone of non-being” – denied full humanity while French settlers occupied the land as its “natural background.”

Albert Memmi’s The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957) analyzed this as a “pyramid of privilege” that created psychological alienation: the colonized could either pursue impossible assimilation or inevitable revolt.

‘Algeria could not find the compass’

Post-independence Algeria inherited this devastated landscape and worsened it through a rigid military regime under Houari Boumediene, which entrenched revolutionary legitimacy, suppressed pluralism, militarized politics, and replaced institution-building with authoritarian myth-making.

The late King Hassan II understood this dynamic with remarkable prescience. In his January 20, 1975 interview with Lebanese journalist Jalal Kachak, he articulated what would become a prophetic diagnosis.

“When peoples are liberated, they need a compass to determine their direction. Algeria’s problem is that it was subjected to colonial oppression lasting several centuries, from the Turks to the French, which destroyed the Algerian personality. Therefore, it lost direction because it could not find the compass – not in its pocket, not in an old library, not in its father’s treasury,” the King said.

He added, with devastating clarity: “It could have leaned on its brothers to the right and left – Tunisians and Moroccans – not so we could give them our compass, for it would not suit them, but so we could help them assemble and determine a compass. But they chose to work alone.”

In this context, Morocco’s identity rests on five pillars Algeria lacks entirely.

First, the Alaouite dynasty has ruled since 1631 – the oldest surviving ruling family in the Arab world. Second, the King in Morocco holds the title “Commander of the Faithful” (Amir al-Mu’minin), providing dual political and religious legitimacy renewed annually through the bay’a allegiance ceremony. Third, the French protectorate (1912-1956) preserved traditional institutions: Resident-General Lyautey learned from Algeria, where “imprudent land appropriation reduced much of the native peasantry to a rootless proletariat.” Fourth, Mohammed V’s exile (1953) and triumphant return made him a personified symbol – the “Revolution of the King and the People” – unlike Algeria’s deliberately faceless revolutionary mythology. Fifth, Morocco recognized Amazigh identity proactively: IRCAM in 2001, constitutional officialization in 2011.

Algeria possessed none of these anchors. No indigenous dynasty – the Ottoman Deylik was ruled by appointed Turkish governors. Complete destruction of pre-colonial institutions. A deliberately impersonal revolutionary mythology. Unresolved Arab-Berber tensions. Power resting on revolutionary legitimacy rather than institutional continuity.

The 2019 Hirak movement revealed these fractures anew: protesters appropriated “one hero, the people” while simultaneously dating the National Liberation Front (FLN)’s “birth” to 1963 – denying its revolutionary origins. Arrests of protesters carrying Amazigh flags demonstrated that identity questions remain explosive.

‘Was there an Algerian nation before French colonization?’

This assessment has proven remarkably prescient. Algeria’s identity crisis is not only a failure of will or leadership but the predictable consequence of 132 years of settler colonialism that destroyed every institution capable of anchoring national identity.

Morocco and Tunisia entered independence with preserved monarchies, functioning traditional governments, and coherent ideological projects. Algeria emerged from an eight-year liberation war – 1.5 million dead – with only the FLN’s mythology: “one hero, the people,” a deliberately impersonal construct that suppressed plurality rather than integrating it.

The scholars who have studied Algeria most deeply converge on this diagnosis. Algeria suffers not merely from bad governance but from a structural inability to answer the question of what it means to be Algerian.

The linguistic crisis (neither truly Arab, nor French, nor Amazigh), the ethnic marginalization (repeated Kabyle uprisings, the emergence of separatism), the civil war (competing claims to Islamic-populist legitimacy), and the Hirak (generational rupture with revolutionary mythology) are all symptoms of this foundational absence.

Where Morocco and Tunisia developed coherent post-colonial ideologies, Algeria substituted mythology for institutions. Where Morocco proactively recognized plurality, Algeria suppressed it until forced to make constitutional concessions.

As a result, Algerian nationalism has failed to remake the nation that colonialism unmade. And instead of genuinely engaging in the patient, painstaking endeavor of building or rebuilding a real sense of national belonging, it has filled the void left by colonization through appropriation. This has meant claiming Moroccan heritage, adopting Tunisian cultural practices, and now boldly rebranding argan as “Algerian” on global platforms.

In this sense, French President Emmanuel Macron’s October 2021 question – “Was there an Algerian nation before French colonization?” – however diplomatically clumsy, touched the neuralgic point of an identity project built, as he claimed, on “memory rent.”

But cultural theft cannot substitute for authentic identity. No amount of borrowed heritage can fill the compass-shaped hole at Algeria’s center.

When that vendor proclaimed “natural Algerian argan” to IShowSpeed’s millions of followers, he wasn’t just making a sale – he was performing Algeria’s deepest pathology in miniature. In a nation still searching for its compass, even borrowed directions seem better than none at all.

Read also: The Makhzen Complex: A Psychoanalytical Decoding of Algeria’s Obsession with Morocco