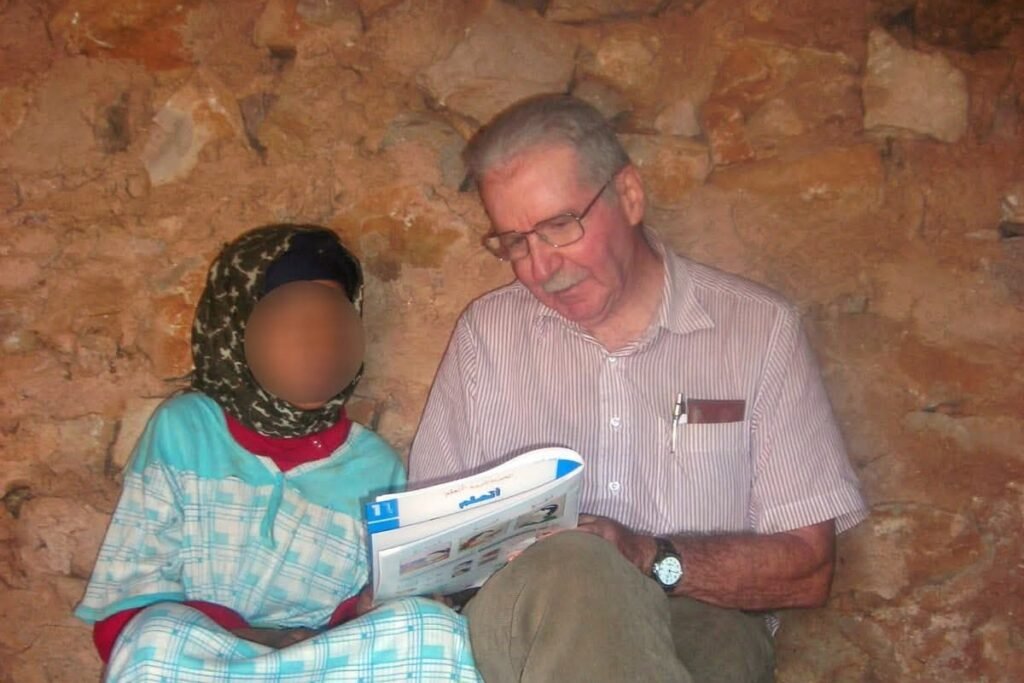

Beni Mellal – For decades, Jacques Leveugle was a familiar figure in the Moroccan town of Khenifra – a thin Frenchman who swept streets at dawn, offered free language lessons, and opened a small library for children. Neighbors called him “Monsieur Jacques.” They trusted him with their sons.

That image collapsed last week when prosecutors in Grenoble, France, announced that the 79-year-old was behind bars and under formal investigation, accused of raping and sexually assaulting 89 boys aged 13 to 17 over more than five decades across nine countries on five continents.

The case has sent shockwaves through Morocco and Algeria, reopening painful conversations about child exploitation in a region where advocates say abuse remains persistent and deeply underreported.

The crimes came to light not through a complaint or a witness, but through a USB drive. Leveugle’s nephew, who had grown suspicious of his uncle’s behavior, searched through five USB drives while the older man was away on a hiking trip.

He found photographs of naked adolescents and 15 densely written volumes of memoirs documenting decades of sexual abuse in meticulous graphic detail. He turned everything over to the gendarmerie of Vizille in 2023. Investigators then pieced together a trail stretching back more than fifty years.

Leveugle confirmed the contents of his writings and was formally placed under investigation and jailed in February 2024. French prosecutors went public with the case on February 10 this year, launching an international appeal for witnesses before closing the investigation.

Across nine countries, five continents

Between 1967 and 2022, Leveugle is suspected of abusing boys in Algeria, Morocco, Germany, Switzerland, Niger, Colombia, the Philippines, India, and France, including New Caledonia. He had no formal diplomas, yet repeatedly secured positions as a teacher, educator, or school assistant.

Grenoble Prosecutor Etienne Manteaux summarized the pattern plainly. “He traveled across these different countries and in each place where he settled to give tutoring or work as a teacher, he met young people and had sexual relations with them,” he told a press conference.

In Morocco, where Leveugle lived until his arrest in 2024, he is suspected of abusing more than a dozen boys, with victims dating back to at least 1974.

In Algeria, where he worked as a French language teacher for eight years during the 1960s and 1970s, at least two children were targeted. French investigators are expected to travel to Morocco to gather further evidence, and the international appeal has been relayed through Interpol.

“I was stunned when I learned that,” Ali Bouchemla, who studied French under Leveugle in the late 1960s in northern Algeria, told the Associated Press (AP). He recalled “a devoted and very good teacher” who never raised suspicion. Another former student, Lahlou Aliouate, described a dedicated instructor with a professional demeanor.

A deliberate and repeated method

Born in Annecy in 1946, Leveugle began his criminal path shortly after turning 21, when he moved to Algeria to teach French. He had studied in preparatory literature classes – hypokhâgne and khâgne – before abandoning his studies and heading abroad.

His method never changed. “He always reproduced the same modus operandi,” Prosecutor Manteaux told Le Monde. “He gave lessons in an associative setting, then identified modest families and entered those families by offering tutoring to the young boys he desired. He was friendly, charismatic, and was welcomed with open arms. He awakened them intellectually, could even finance a driving license like a generous godfather, but gradually he imposed caresses.”

Over the years, he supervised educational stays for delinquent children in Germany, worked as an educator in Bogotá, ran youth camps, and led sporting activities including canyoning and caving.

Leveugle first arrived in Morocco in 1955, when his father worked at the French Embassy. He settled in Khenifra’s working-class Lassiri neighborhood in the early 2000s, where he spoke fluent Arabic, Moroccan dialect, and Chelha, the Tamazight variant widely spoken in the region.

He rode his bicycle to market, dressed simply, funded local projects, helped residents find jobs, and sometimes handed out cash in a town long struggling with high unemployment. He organized school outings and offered free tutoring to families who could not afford private lessons.

Residents recalled one outing to the regional lake of Agelmam Agezga, where Leveugle told the children to swim naked, claiming it was healthy.

In Moroccan and broader Islamic tradition, public nudity between men is culturally and religiously prohibited; modesty is deeply ingrained, and exposing one’s body in front of others is simply not part of accepted social conduct. At the time, no formal complaint was filed.

No criminal proceedings had ever been opened against him in Morocco before his arrest.

A man who theorized his own crimes

In his memoirs, Leveugle – who describes himself as a “gentleman boy lover” and considers himself a man of letters – did not simply record his crimes. He justified them.

The prosecutor told Le Monde that Leveugle “intellectualizes his inclinations by comparing himself to the Greeks, to André Gide or to Montherlant, and considered that he participated in the intellectual and sexual awakening of his victims.”

He claimed to have the sexuality of a 14-year-old boy. He imposed caresses and oral sex on his victims, but the case file contains no evidence of complete sexual intercourse, according to the prosecutor. When his victims reached 16 or 17, he ended each relationship. Homosexuality with an adult, he wrote, repulsed him.

Of the roughly forty victims identified and interviewed so far, most expressed ambivalence. They described a man who had “opened new horizons” for them, teaching them foreign languages, introducing them to books, and taking them to museums. Only two have filed as civil parties.

Years of impunity, explained

The sexual abuse was not Leveugle’s only admitted crime. In his memoirs, he recounts smothering his mother with a pillow in 1974, when she was in the terminal phase of cancer, claiming he wanted to end her suffering.

In 1992, he did the same to his 92-year-old aunt in Switzerland, who suffered from no serious illness but had begged him to stay with her during a visit. Unable to remain, he suffocated her in her sleep. He justified both killings to investigators by saying he would want the same done to himself at the end of his life. A separate investigation has been opened for both homicides.

How Leveugle evaded justice for 55 years is a question investigators and legal experts are now confronting directly.

A police source told the French outlet 20 Minutes that the crimes occurred abroad, many were very old, and complaints were rarely filed. “There are countries with which it is complicated, which are not very cooperative,” the source said, pointing specifically to Maghreb countries.

Paris-based lawyer Céline Astolfe, who has represented victims of similar predators, was blunt. “The difficulties encountered in international judicial cooperation leave room for a form of impunity for this type of predator,” she said. “There are major difficulties with the execution of letters rogatory. Countries well known to French judicial authorities do not respond to requests.”

Unlike many modern predators, Leveugle never exchanged his files online. He kept everything on USB drives, which meant he never appeared on the digital radar of law enforcement.

“He probably felt untouchable far from France,” said retired General François Daoust, former director of the gendarmerie’s judicial division. “But the law has evolved, and you can now be prosecuted for acts committed abroad.”

Calls for victims to come forward

Child protection organizations say Leveugle’s profile fits a well-documented pattern. “Perpetrators often present themselves through educational or cultural activities, cultivate a respectable image and leverage social or cultural prestige to gain trust,” said Najat Anwar, president of Moroccan child protection association Don’t Touch My Child. “They then target children in vulnerable emotional or social situations.”

Anwar told the Morocco World News (MWN) her organization is prepared to join the case as a civil party if Moroccan witnesses or victims come forward.

“We will not protect the aggressor through silence,” the organization affirmed in a statement earlier this week, urging potential victims, direct or indirect witnesses, and anyone holding relevant information to contact them without delay.

The organization assured full confidentiality to all those who reach out, pledging psychological support and legal assistance where needed.

“Any piece of information, however small it may seem, could be decisive in delivering justice to the victims,” the statement read, adding that “silence does not protect society – it gives the aggressor the opportunity to escape accountability.”

Prosecutors estimate that nearly half of the 89 identified victims – around forty – have been located and interviewed. French authorities believe the true number of victims is higher. The Interpol-relayed appeal for witnesses remains open.

Back in the Lassiri neighborhood, residents say their sense of shame is difficult to carry. Many are considering leaving. The unfinished house where Leveugle lived, surrounded by fig trees alongside a river, still stands. Children play nearby.

The investigation continues.