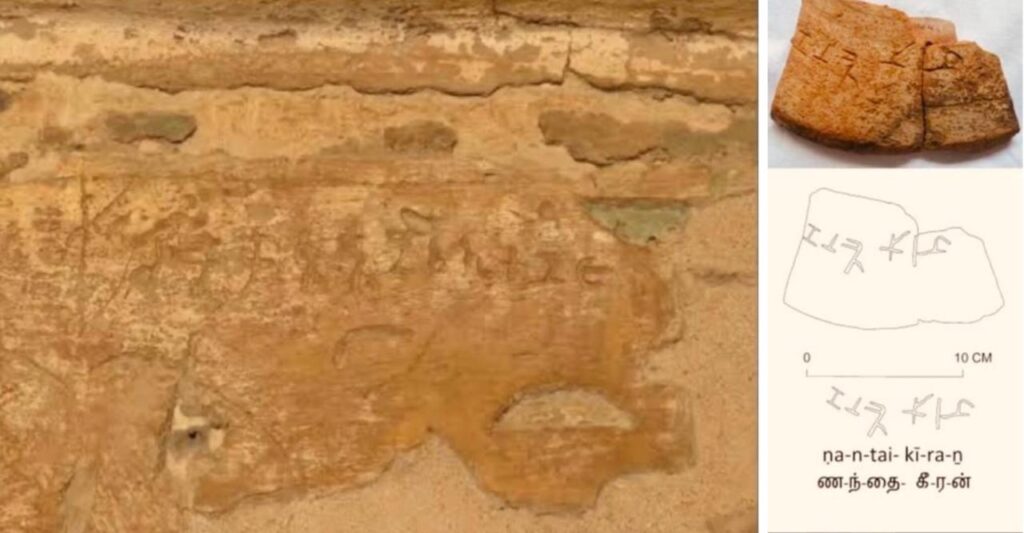

Recent archaeological findings, shared by Swiss professors Ingo Strauch and Charlotte Schubert alongside Indian archaeologist Dr. Ramakrishnan and Tamil Nadu Minister Thangam Thenarasu, have reignited curiosity about ancient transcontinental networks. The reported discovery of the Tamil name “Sigai Kottran” in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings suggests deeper Tamil-African interactions than previously understood, highlighting the possibility of significant historical exchange between the two regions.

While such claims require rigorous peer review, epigraphic verification, and scholarly scrutiny before firm conclusions can be drawn, the broader question they raise is profoundly significant: how interconnected were ancient civilizations across Africa, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean world?

This inquiry extends beyond Egypt. It invites renewed exploration into North Africa including Morocco as part of a wider Afro-Asian maritime system that predates modern globalization by millennia.

The Indian Ocean: The World’s First Global Highway

Modern maps often distort our perception of ancient connectivity. What appears today as vast oceanic separation once functioned as a dynamic corridor of exchange. The Indian Ocean was not a frontier; it was one of humanity’s earliest highways.

Classical Greco-Roman texts such as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea describe structured trade networks linking Roman Egypt with the western coast of India. Ports such as Berenike and Myos Hormos on Egypt’s Red Sea coast received pepper, pearls, fine cotton textiles, gemstones, ivory, and exotic animals from South Asia.

Archaeological excavations in Berenike have uncovered black peppercorns from India dating to the first century CE. Meanwhile, Roman gold and silver coins have been found in large quantities across Tamil Nadu, particularly in Karur and Arikamedu, suggesting not sporadic contact but sustained commercial engagement.

Trade was rarely one-dimensional. Alongside goods came language, religious ideas, artistic styles, and technological knowledge. Maritime traders were often cultural intermediaries. In this sense, the Indian Ocean was never a barrier but a bridge.

The Tamil Maritime Legacy

Ancient Tamilakam, governed by powerful dynasties such as the Cholas, Cheras, and Pandyas, possessed sophisticated naval capabilities. Sangam literature — composed roughly between 300 BCE and 300 CE — contains references to overseas trade, foreign merchants, and bustling port cities such as Kaveripattinam.

The Chola naval expeditions into Southeast Asia during the 11th century CE further demonstrate that South Indian polities had both the logistical capacity and maritime ambition to engage distant regions.

Given this maritime dynamism, it is plausible that Tamil traders were integrated into broader Afro-Eurasian networks extending beyond the Red Sea. Whether directly or through intermediary trading hubs, goods and possibly individuals moved across interconnected systems spanning East Africa, Arabia, and the Mediterranean basin.

If a Tamil name such as “Sigai Kottran” were to be academically confirmed within Egypt’s archaeological context, it would not be an isolated anomaly. Rather, it would fit within a wider pattern of documented Indian Ocean exchange.

Egypt as a Gateway

During the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, Egypt functioned as a central node connecting Africa, Asia, and Europe. Its ports were gateways between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.

But Egypt was not the only North African participant in transcontinental trade.

Overland and maritime networks extended westward along the North African coastline. Carthaginian and later Roman trade routes linked the Maghreb with Mediterranean markets. Trans-Saharan trade routes connected West Africa’s gold fields with North African urban centers.

This broader geography invites a compelling question: could elements of Indian Ocean trade have extended further west into North Africa’s Atlantic and Mediterranean corridors?

Morocco as a Crossroads of Civilizations

Morocco occupies one of the most strategic positions in the ancient world. Situated at the junction of Africa, Europe, and the Atlantic, it has historically served as a crossroads of civilizations.

From Phoenician settlements to Roman cities such as Volubilis, from Amazigh cultural foundations to Arab-Andalusian influences, Morocco’s historical landscape is layered and multidimensional.

The intellectual journeys of Ibn Battuta in the 14th century illustrate Morocco’s outward-looking character. His travels across Africa, the Middle East, India, and China demonstrate that pre-modern mobility was far more expansive than often assumed.

Additionally, Morocco’s integration into trans-Saharan trade networks connected it to West African gold, salt, and caravan routes that ultimately intersected with Mediterranean commerce.

While no definitive archaeological evidence currently links ancient Tamil traders directly to Moroccan shores, the logic of interconnected trade systems suggests that North Africa was not isolated from wider Afro-Asian economic flows.

Systematic collaborative research involving Moroccan, African, European, and South Asian scholars could illuminate overlooked dimensions of early maritime and caravan networks.

Rethinking Historical Silos

Modern historiography often compartmentalizes civilizations: Egypt studied separately from India; North Africa separated from the Indian Ocean; sub-Saharan Africa isolated from Mediterranean narratives.

Yet, emerging scholarship increasingly challenges these artificial divisions.

The ancient world was interconnected through trade winds, caravan routes, and shared economic incentives. Ports, not borders, defined interaction. Merchants were often multilingual intermediaries bridging cultures long before the rise of nation-states.

The possibility of Tamil–Egyptian linkage is therefore less about one inscription and more about reframing how we conceptualize ancient global systems.

If validated, such discoveries would support the understanding that Afro-Asian engagement was not peripheral but foundational to early global exchange.

A Responsibility to Uphold

It is essential to emphasize academic rigor. Archaeology demands careful excavation, carbon dating, epigraphic analysis, and peer-reviewed publication. Extraordinary interpretations must be supported by extraordinary evidence.

Public enthusiasm should not outpace scholarly verification.

However, responsible curiosity should not be discouraged either. New discoveries often challenge long-held assumptions.

The Valley of the Kings discussion – whether ultimately confirmed or revised – has already served a valuable purpose: it has reopened scholarly interest in Afro-Asian interconnectivity.

Why This Matters Today

In a contemporary world marked by geopolitical fragmentation, rediscovering shared civilizational roots carries powerful symbolic value.

India and Morocco today maintain cordial diplomatic relations grounded in mutual respect and South-South cooperation. Exploring potential ancient connections adds cultural depth to modern partnerships.

More broadly, understanding Africa and Asia as historically interconnected reshapes global narratives that have often centered Europe as the primary axis of exchange.

The Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, and the Atlantic were never civilizational edges, they were connective arteries.

The Unexplored Possibilities

Much of Morocco’s archaeological potential remains underexplored. Coastal sites, submerged ports, and caravan hubs may yet yield findings that contribute to a broader understanding of Afro-Asian interaction.

Collaborative research initiatives combining marine archaeology, trade-route mapping, linguistic studies, and material analysis could unlock new perspectives on ancient connectivity.

Such work would not seek to prove predetermined conclusions, but to explore evidence with open inquiry.

Civilizations do not evolve in isolation. They grow through encounters.

Whether the name “Sigai Kottran” ultimately withstands academic scrutiny or not, the larger truth remains: ancient societies were more mobile, interconnected, and cosmopolitan than modern narratives sometimes suggest.

Reexamining these networks is not merely an academic exercise. It is a reminder that human history has always been collaborative.

As the late King Hassan II once said, “Morocco is a tree whose roots lie deep in Africa, whose leaves reach toward Europe.” These branches, carried by ancient trade winds, touch the shores of the Indian Ocean and the Tamil civilization.

Perhaps, beneath the sands of North Africa and along Morocco’s ancient shores, more stories of this shared humanity remain waiting to be uncovered.